Posted in 2019

Using the Zeiss-Abbe polarizing attachment for their 19th century microscopes

It’s now over a year since I described how to use the Abbe polarizing attachments with one of our late 19th century jug-handled microscopes. Since then, I’ve had one disappointment. The attachment does not fit any of our more “modern” (ie 20th century, with electricity) microscopes and I’ve had to continue using the mirrored model.

My original attempts to use them all employed thin mineral slices because I wanted samples with known, reliable reactions to the polarizing light, but then I started considering what they were actually used for in Microbiology or Botany laboratories. We have at least 20 of the adaptors, plus a number of partial or damaged kits, so they must have originally been used for teaching before WW1. It seemed a good idea to test their performance with biological samples.

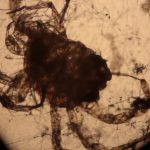

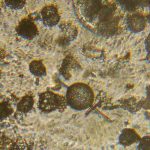

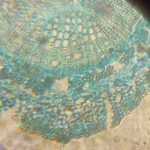

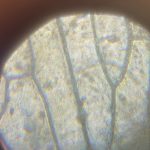

In all of the image pairs presented here, the first image is without polarization, and the second with it.

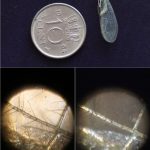

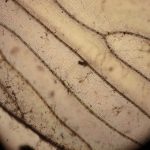

The first image set (above) shows two of my standard microscope-testing samples (very useful for comparisons). The insect is a lacewing and the sample came from one of its wings. Despite the fact that the lacewing has been dead at least 2 years (it was “rescued” from a spider’s web), the veins gave clear, silvery-white fluorescence with polarising light. The thin section is a commercially bought, stained section of a plant stem. From comparisons with other samples, it is the stains that fluoresce, not the fixed plant tissue.

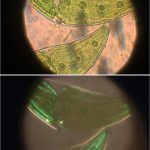

The remaining images (above) were made with living algae (Closterium sp.) at 2 magnifications (Zeiss lenses C and D, but their magnifications need to be recalibrated because of the distance of the camera’s sensor from the lens). It appears that only sections of their chloroplasts were fluorescing. The sample had been taken a week previously from a pond in the area where the Berkelsemeer (Van Leeuwenhoek’s first microbial hunting ground) used to be.

Guessing from the location of the cupboards where we found the attachments, it seems likely that they belonged to the Botany department. We’ve recently found a few of their practical handbooks in the archive – maybe one day I’ll be able to try the attachments with the original experiments! First, I want to try the other microscopes in our collection.

Playing with our Nuremberg microscope

There is a great deal of fun to be had from working with old microscopes whose instruction books are lost in the mists of time (if, indeed, they ever existed), whether it’s a single lensed microscope from the 17th century, or something a little newer. There is a lot to be learned, not only from how they were used, but also from their limitations. Modern digital cameras also make it much easier to record results.

Some of the wet Sundays of this winter have been spent on the Collection’s Nuremberg microscope. Since it is made mostly of wood, cardboard and shagreen (and the glue used in its construction is failing), after over 200 years it is far too fragile to take apart completely for cleaning. It can’t withstand my usual use of a camera body (Canon M10 or M6) mounted on an adapter in place of the ocular. Instead, I used a small tripod and a digital camera body fitted with a macro lens so that nothing had to touch the microscope. This had the advantage of providing images as the microscope had been used, with both of its own lenses. The mirror is in reasonable condition, and was lit with the LED lamp used in previous experiments. One word of warning for anyone else with one of these microscopes. The little glass lens was not attached to its wooden holder and fell into my working tray as I opened the lens holder. Whether this was normal, or whether the glue used to hold it in place has completely deteriorated, I don’t know. There was none visible on the lens or holder.

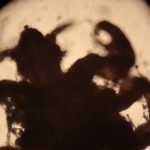

Nuremberg microscopes are frequently provided with small wooden sliders containing pre-mounted samples. One of these can be seen to the left of the microscope in the first photograph, above. Using the sliders with this microscope was very frustrating as only shadowy outlines could be seen.

Checking the sample slider with a 20th-century Olympus microscope revealed that most of the samples had either broken up or were just shadows in the adhesive holding the slide together. The 3rd of the set below is the only one that gave even a reasonable image.

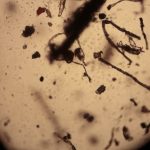

Better results were obtained when I tried modern slides with the Nuremberg microscope. On the left, below, diatoms, and on the right, a stained section through a plant stem.

The insect wing image on the left, below, was made using the Nuremberg microscope, the image on the right is the same sample photographed through the Olympus microscope. Focus with the Nuremberg was difficult because it requires moving one cardboard tube up and down inside the other and, as already mentioned, the microscope is extremely fragile.

Considering that this microscope was made by a woodcarver over 200 years ago, presumably as a copy of a brass microscope, I was pleasantly surprised with the quality of the images of modern samples, especially since I had previously tried it with the sliders and concluded that the microscope really wasn’t very good.

It is now back in its display cabinet for safekeeping.

And I’m wondering what to try next!

Recent Comments