Posted in 2017

Exploring the Delft School’s microscope collection – 1.

As I have mentioned before, the Delft School of Microbiology Archive has a small collection of old and unusual microscopes. We also have a range of attachments with varying (and sometimes unidentified) functions as well as two boxes of mysterious parts. One of my projects for this winter is to try as many of these things out as possible, and write a methods book for the collection.

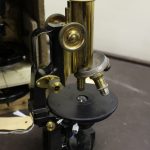

I have started with two red boxes from Ernst Abbe’s time at Carl Zeiss Jena (CZJ). Abbe was one of the founding fathers of CZJ and the inventor of many microscope techniques that we take for granted today, including standardizing lens quality. One of the boxes contains the parts necessary to convert a simple microscope for work with polarization, the other contains a camera lucida. Both were obviously routinely used in the times of Beijerinck, Van Iterson and Kluyver and we have enough of each for every student in a practical class to use them. None of the boxes included instructions, and nobody I’ve asked had tried to use either one. Since they turn up sometimes on auction sites, it seems to be worth outlining my findings here. I used my late 19th century jug-handled CZJ microscope.

- Abbe's polarizer

- Abbe's camera lucida

- My CZJ microscope

The polarizer.

The box contains a polarizer (top right in the photo), a calibrated ring (centre) and an eyepiece (bottom left). It took me a while to realize that the polarizer is actually two pieces which unscrew. The piece with the lens fits into the filter ring under the condenser, and the ring screws on underneath the filter ring to stabilize the polarizer. The calibrated ring fits around, and the eyepiece over the ocular.

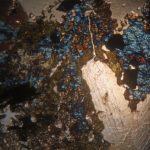

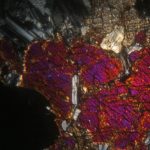

Using my usual LED lamp, I adjusted the mirror and condenser to give optimum light and then inserted a slide. Rather than microorganisms, for these experiments it was simpler to use samples guaranteed to give the dramatic colour changes associated with polarizing microscopy and so I chose mineral samples prepared for the microscope by Dr F Krantz of Bonn around the beginning of the 20th century (and also in our collection). The pairs of photos show the extremes of uncrossed and crossed polarized light paths for 3 different minerals.

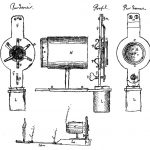

The camera lucida

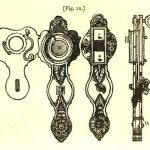

The box contains a ring which fits over the microscope’s ocular. Attached to the ring is an arm with a mirror at its end and a shorter, moveable arm supporting the prism that combines the images from the microscope and the mirror. The arm allows the prism to swing over or away from the ocular, allowing the microscope to be used with and without it (very useful for focusing and sample placing).

Initially, I found this attachment very frustrating because everyone I had discussed it with confidently said that it projected the sample’s image onto paper beside the microscope. This did not happen. It was only when I looked through the ocular to check the microscope’s focus and saw a ghostly pen superimposed on the sample that I realised that the projection was the other way round! Thus far, I am not very satisfied with my photographs of the combined images, but I’ll post a picture here when I’m happy with them. The problem is not in using the equipment, but in convincing the camera that it can focus on the pen and sample at the same time – I see that CZJ’s catalogues of the time also offer a drawing platform for use with their camera lucida which was presumably exactly the correct height. If anyone wants to try, I’ve had better results with cream coloured paper rather than bright white paper which tends to reflect more in the field of view. Reducing the light in the room also helps.

Van Musschenbroek Microscopes

It cannot be denied that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek made major discoveries with his single lensed microscopes. Consequently, when thinking about the simple microscopes of the 16th and 17th centuries, most people have focused on his very simple (some say crude) microscopes. In fact, there were several other single lensed microscopes in use at the time. Many of them were more complicated than Van Leeuwenhoek’s microscope with extra features and even engraved ornamentation. One had a rotating disc with different sized holes to give varying apertures, others had detachable lenses or moving sample holders so that samples did not have to be transferred to another microscope for a change of magnification. Significant discoveries were also made with these microscopes and yet they are rarely studied. Comparison of results from the different types could tell us so much more, but working replicas (with proper lenses) like the Van Leeuwenhoek replicas I normally work with are not to be found.

- Kircher

- Huygens 1

- Huygens ver 2

- Joblot

- Hartsoeker

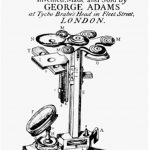

- Adams

Last year, after I complained about the lack of such replicas for experimental use during a lecture, someone called my bluff. Dr Koen Quint of the Dutch Stichting voor Historische Microscopie offered me the honour of trying their (real) Van Musschenbroek microscope! I have to admit that my first reaction was panic.

The Van Musschenbroek workshop in Leiden was a family business between 1660 and 1750. They produced (and invented) a range of scientific instruments, among which were microscopes. At its peak between 1730 and 1740, their microscope range included 10 different models, some of which were their own invention. The more complicated of their single lensed microscopes included a holder and detachable lenses.

Van Musschenbroek microscope with lenses and sample holders

The initial experiments have been encouraging. Of course, using a centuries-old microscope was a bit nerve wracking, and much of the first session was spent working out how to set everything up without damaging it (e.g. we wrapped the handle of the microscope in felt to protect it against the clamps holding it erect). Obviously I can’t take it home to use on wet Sunday afternoons as I would with a replica, but the next few weeks are going to be fun!

Van Iterson’s wall chart collection.

In the days before the easy projection of images, wall charts were the usual manner of illustrating lectures and practical classes. This photo shows the autumn 1941 practical on microscopical research of living plants and plant products, with wall charts in use on the back wall. Prof van Iterson can be seen standing in the far left corner of the room.

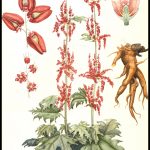

The Archive has a large collection of these wall charts, and I’ve previously shown some of the printed ones as well as some by Henriette Beijerinck. The original wall charts for Van Iterson’s Department were produced by at least 15 people, not all of whom signed their work with their full names. They range from beautiful watercolours of useful plants to diagrams and tables – everything a Professor of Applied Botany could need for his lectures.

- Ornamental rhubarb by Karin Mauve, 1920s

- Poppy by Hilda Kern, 1940s or 50s

- Almonds by ? Bongers, 1923

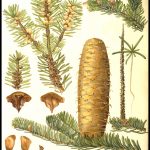

- Silver spar pine by J. Mouton, 1920s

- Peanuts by Sluyterman, 1920s

- Cotton by Karin Mauve, 1920s

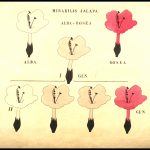

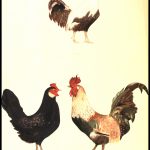

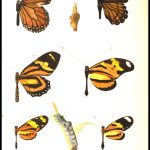

Like Beijerinck and Kluyver, in those days before the discovery of DNA, Van Iterson was interested in heredity and variation, and we have a series of watercolours illustrating Mendelian genetics, gender dimorphism and mimicry.

- Mendelian cross of white and pink Mirabilis jalapa. Unknown.

- Cross of Italian and Plymouth Rock chickens

- Butterfly mimicry by J. Mouton, 1920s?

Researching and cataloguing the wall chart collection was a great labour of love by Truus ten Hoopen-van Hulsentop. If anyone can tell us anything more about the various artists, we’d be delighted to hear from you.

Something Van Leeuwenhoek didn’t see!

On 7th May (2017) the Dutch Society for Microscopy (Nederlands Genootschap voor Microscopie) ran an open microscopy workshop at the Delft Science Centre. They taught members of the public (and me!) how to make thin sections of plant material, stain the sections and then examine them under modern microscopes.

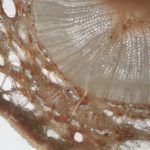

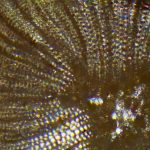

The plant material in question was a twig from Wollemia nobilis (captive bred). W. nobilis is a very rare pine tree that was only known from the fossil record until 1994 when a few trees were found in Australia. The oldest tree has been estimated to be over 1000 years old according to the Kew Gardens website. As the only representatives of a genus that dates back to the time of the dinosaurs, the wild trees are IUCN-red listed and stringently protected, but seedlings can now sometimes be bought.

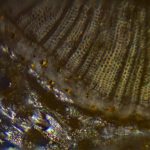

Since there were a few sections left at the end of the workshop, how could I resist putting them under my 65x facsimile Van Leeuwenhoek microscope? He would, of course, have examined them if they had been available to him 300 years ago.

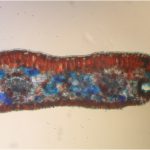

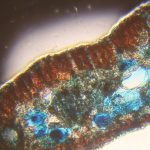

A couple of images using a much weaker lens on my 19th century Zeiss “jug handled” microscope have also been included for comparison (the first photo on each line). The red and blue images came from a stained preparation, the others from a section that had been allowed to dry on a coverslip, without staining.

- Stained needle section under the Zeiss

- Stained needle section under the AvL

- Stem section under the Zeiss

- Central area of stem section under the AvL

- Outer area of stem section under AvL

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek in Spain

I have just heard that it will be possible to see part of the beautiful Camacho & Pallas microscope collection at the Museum of Evolution in Burgos (Castille & Leon) in Spain.

http://www.museoevolucionhumana.com/

The exhibition will run from April to November, 2017.

This is a privately-owned collection which includes the Van Leeuwenhoek microscope that was found in mud dredged from Delft’s Oude Delft canal in in 2015 (see my blogpost from 23 June 2015).

If you’re going to be holidaying in Spain this summer, it’ll be well worth a visit.

Beijerinck’s office (and the neighbours)…

At long last, the Beijerinck Museum is ready for visitors – indeed several groups, including the Dutch Microscopy Society and guests from the Queckett Microscopical Club, have had sneak previews. Also known as “Beijerinck’s Office” (Kamer van Beijerinck), it will only be open to escorted groups as we don’t want to spoil the atmosphere by putting everything into locked display cabinets. Some of our microscopes are now on display in the foyer of the Mekelzaal, the main conference room of the Science Centre.

- Beijerinck's office 2

- Beijerinck's office 1

- Microscope display

- Monuments to Beijerinck, Van Iterson, Kluyver and Van Rossem

At the end of BioDay, a meeting organised to celebrate the TUDelft’s 175th birthday, the Museum was re-opened by Professor Karel Luyben, Rector Magnificus of the University, ably (?) assisted by someone claiming to be Prof Beijerinck’s assistant…

- Opening the museum

- Bioday

This seems like a good moment to take a look at our new surroundings. We are housed on the second floor of the Delft Science Centre. The building was originally the Faculty of Mining. It’s very easy to feel at home here as, like Prof van Iterson’s section of our previous building, our new home dates from the early 20th century and the design is very similar. The view from our windows is a great improvement!

- Science centre

- Mining

The main part of the Science Centre displays the modern achievements of Delft University of Technology and a range of prototypes (including Delft’s famous solar powered car) can be seen as well as displays that can be operated by the visitors. You can try improving the shape of an aircraft wing or use the driving simulators, among many other things – the exhibition often changes. The robotics lab is ever popular, as are the workshops where school groups (among others) come to try things out. For example, the Dutch Microscopy Society will be running a public workshop (about how to make botanic preparations (Wollemia nobilis) and look at them under the microscope) from 14:00-16:30 on 7th May (2017). Participants will only pay the Science Centre entrance price. The details are here: www.sciencecentre.tudelft.nl/nl/bezoek/agenda/event/detail/gratis-microscopie-workshop/. It’s in Dutch but the site will allow you to copy the text for pasting into Google translate (which is always amusing….).

- The Science Centre's main hall

- climber

- Robotics

The TUDelft has always had a number of internationally important collections which started life as the working tools and products of its research departments. Among them, the minerals collection from the Faculty of Mining (which dates from the middle of the 19th century) is remarkably beautiful. It is housed, in its original display cases, in rooms next door to the Beijerinck Museum and in cabinets in other public parts of the building. Like the Beijerinck Museum, the Minerals Collection is open to escorted groups.

- Minerals museum

- Minerals exhibition

- Garnets

- Amethyst

Just around the corner from the Science Centre is Delft’s Botanic Garden. Founded by Prof van Iterson with support from Prof Beijerinck, it was set up to provide plants for research in the Department of Applied Botany and is 100 years old this year (2017). Apart from their permanent collection (which includes an apiary), they frequently have exhibitions ranging from pottery through products made from plant material to photography. Their website is here: http://www.botanischetuin.tudelft.nl/en/

- Botanic garden

- Garden entrance

The Science Centre’s website with opening times and other information is here http://www.sciencecentre.tudelft.nl/en/.

Delft, the Home of Microbiology

An exhibition at Van Leeuwenhoek’s resting place.

2017 is the 175th anniversary of the founding of the Polytechnic School that eventually became Delft University of Technology. The University is celebrating with a 175 day Lustrum, much of which will focus on the Life Sciences. It is also 100 years since Van Iterson founded the Delft Botanic Garden on the land behind his laboratory.

We are beginning the celebrations with a look at the history of microbiology and the biosciences in Delft, from the 17th to the 21st centuries. The exhibition will run until 26 February, 2017.

This will take the form of an exhibition in the area around Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s grave in the Oude Kirk.

- Delft's Old Church

- AJ Kluyver at the grave of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

The text on the poster boards is in Dutch, but there are also English language handouts. It includes 20th century teaching microscopes, a cross section of an electron microscope and 3-D scanned replicates of a Van Leeuwenhoek microscope and the Delft telescope.

The exhibition offers a taster of the achievements of Delft microbiologists and introduces some of the people who helped and supported them. For example, we might never have heard of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and his little animals without Reinier de Graaf, the doctor who introduced van Leeuwenhoek to the Royal Society of London, publishers of much of his work. Jacques van Marken not only brought Beijerinck to Delft to establish his industrial microbiology laboratory, he was also one of the people instrumental in creating the Department of Microbiology and Professor’s Chair for Beijerinck at what was then the Delft Polytechnic.

- Reinier de Graaf

Medicinae Doctor

- Jan and Agneta van Marken

Many others have provided help, support and encouragement, but the silent contributor to the history of microbiology is the City of Delft itself. Many very well-studied microorganisms were found for the first time in samples from Delft’s canals, soil and from industrial sources, even now.

- Th old city gate

- Wastewater bioreactors

Over 300 years ago, before Van Leeuwenhoek found his little animals, the city was already a hotspot in scientific research-for example Stevin and de Groot dropped different lead balls off the tower of the New Church and proved that they hit the ground at the same time 3 years before Galileo did the same experiment from the tower of Pisa!

Recent Comments