Posts tagged Leeuwenhoek

Playing with facsimile Van Leeuwenhoek microscopes

Since most of my available time is currently vanishing into preparing the Delft School Archive and Museum for its move to Delft’s Science Centre, I thought that a simple blog showing some of the photos I’ve taken with my facsimile Van Leeuwenhoek microscopes might be nice this month.

By the way, I’ve been asked why I keep the photographs on this blog fairly small. The reason is simple – I’ve had some problems with plagiarism and this is an attempt to limit what people can do or claim with my work without the high resolution versions.

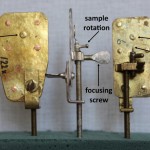

I have 5 Van Leeuwenhoek facsimiles with magnifications ranging from 68x-303x, and have been trying to repeat some of his experiments as closely as possible (it’s a good way to spend a wet weekend!). The first 2 pictures show the structure of the microscopes and my photographic setup. Ideally, one needs a camera that can cope with single point metering, and a macro lens also helps with short focusing distances. The microscope is clamped in front of the camera lens, side-on. The piece of cardboard (with a 1 cm hole in it) is there to protect the camera’s light meter because that lamp was much bigger than the microscope. I’ve recently been finding it easier, especially with the stronger lenses, to use a small LED torch.

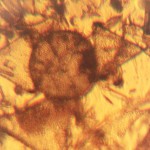

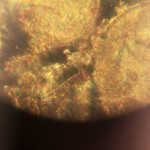

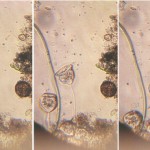

Fossil microorganisms can be very useful for comparing methods as they don’t dry out, swim away or otherwise change. Here you can see a vorticella-type protozoan (L) and diatom preparations under bright (C) and semi-dark field (R) lighting

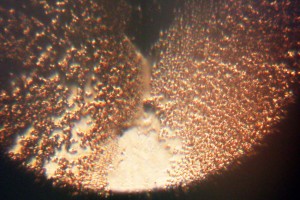

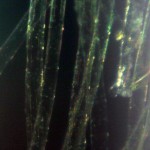

Van Leeuwenhoek’s first observation of microorganisms came from his examination of a water sample from a shallow lake called the Berkelsemeer. This lake no longer exists, but a sample from a similar lake near Delft (the Delftsehout) provided this picture (one of the first I took) of blue-green algae and a rotifer on the right. The black circle is an air bubble.

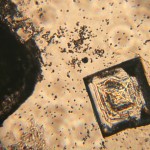

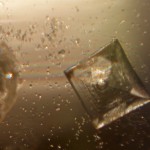

Van Leeuwenhoek did a lot of work on the formation of crystals of different sorts, and the next 2 photographs show the same table salt crystal under bright (L) and semi-dark (R) field lighting. My results agreed with Van Leeuwenhoek’s observation that you get smaller crystals if you let them form slowly by letting the saturated solution evaporate at room temperature rather than by heating it.

The next picture shows red blood cells that I’d dried onto a coverslip. I only noticed after I’d taken the photograph that the little torch had slipped a bit, but I rather like the odd lighting effect.

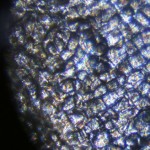

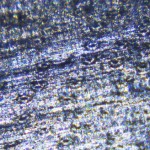

Thus far, my attempts to make thin enough slices of plant materials to examine properly have not been very successful. These photos show my best efforts for carrot root (L) and leek leaf (R). I’m reluctant to cheat by using a microtome, so will have to keep practising!

As Van Leeuwenhoek also complained, the shallow depth of field (or focus) of the stronger microscopes can be a real problem. I haven’t been very successful with taking photos of living microorganisms using the 303x lens. They tend to swim out of focus before I have time to trigger the shutter, so the least frustrating thing is to make short films and then use single frames from the film. This image shows bacteria and a hunting ciliate protozoan from a pepper water sample.

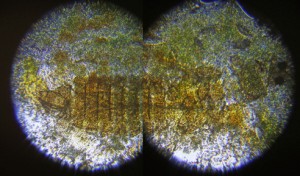

Finally, a lobster larva from a seawater sample. It was either long dead, or a shed skin as the whole thing was covered by a thin layer of algae. I had to take 2 photographs and then join them afterwards– I obviously need to get a weaker microscope!

Delft’s Biological Labs 2: The originals..

Sadly, there are no pictures of the first “microbiological laboratory” and the building was demolished at the start of the 1890s, but by collecting the occasional descriptive comments from Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s letters, we can gain a glimpse of the room where so many types of microorganism were seen for the first time. The following is an extract from our book “Antoni van Leeuwenhoek: Master of the Miniscule” which is scheduled for publication by Brill, Leiden (Brill.nl) in April, 2016.

Van Leeuwenhoek’s home and workshop

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek worked in his comptoir. The word literally means a counting or writing room, but it was actually his workshop. It was located in an annex to his house so that he would not be disturbed. The room was partitioned off with wainscoting, with a hole to accommodate the spring pole of his lathe. The bottom two of the four windows overlooking the street could be opened upwards, and were fitted with wooden shutters. His workshop could be closed off “so that little or no air enters from outside”, but if he was working with a candle, he preferred to open them a little, and cover the window with curtains.

His letters and the inventory of the house compiled after the death of his daughter Maria reveal some of the equipment and materials that he used. As well as his lens and microscope making equipment, there was a small furnace to extract gold and silver from ore, a barometer, a salt water aquarium, sharp blades, chemicals (including the distillate “brandewijn” for conservation and saffron for colouring), and a collection of specimens ranging from minerals to the testicles of a rat preserved in spirits. He had a balance with weights, a glass-blowing table with a lamp, and an anvil for the production of his microscopes, and all of his surveying equipment.

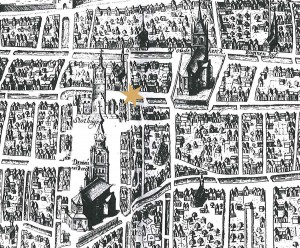

Many of the objects that Van Leeuwenhoek studied came from the immediate surroundings of his home. He had two gardens, one adjoining the house with a well and another outside the city. He kept a green parrot for a long time and examined the excrement of the sparrows in his yard after feeding them. Delft’s fish market was just across the canal from his house. Since he regularly attended the dissection demonstrations at the neighbouring Anatomy Theatre, it seems likely that he brought samples home. Additionally, in a few of his letters he mentioned that sailors returning from voyages brought him exotic samples.

The star shows the position of Van Leeuwenhoek’s house in relation to the Town Hall, where he worked, the marketplace and the Old Church where he is buried.

The Microbiology Laboratory

Beijerinck originally came to Delft in 1885 to set up and run a microbiological laboratory in J.C. van Marken’s Yeast Factory. Van Marken and his wife were enlightened employers, providing their workers and their families with on-site houses, education, medical and social facilities. Van Marken made it a point of honour to keep all of his staff informed about the factory by means of an internal paper called “De Fabrieksbode”. In 1885 he wrote an article about the need for proper bacteriological studies, edited extracts of which follow:

“I would like to explain the need for the appointment of Dr. Mr. W. Beijerink as Chief of the Bacteriological Laboratory of the Yeast Factory…..

I have previously discussed the idea that “life is a struggle”, in this case between yeast and against harmful bacteria. The day on which the last harmful bacteria has been expelled from our

factory will be a cause for celebration and a public holiday….

We would have a quality supply of yeast, which would overcome the sharpest competition; our yeast would be able to circle the world in 80 days, without spoiling.

So fight the harmful bacteria!“

Van Marken’s attitude to results seems remarkably relaxed, contrasting with the attitudes of modern industry. He went on to say:

”Whatever the case, the arrival of the scholar, Dr Beyerinck must be appreciated in more ways than one. We must not have exaggerated expectations of his activities in and for our factory, but have faith that in maybe one, five or even ten years, some day a ray of light will be cast into the darkness of the fermentation business and bring incalculable advantages to our company.”

It cannot be claimed that Beijerinck was happy as an industrial scientist. He felt responsible if errors incurred financial losses, and his interests were much wider than required by his job. As can be seen from the table below and his laboratory journals, he seems to have normally had several unrelated lines of research running at any one time. Only the rows marked * involved work needed by the Factory.

TOPICS OF PUBLICATIONS THAT APPEARED DURING BEIJERINCK’S INDUSTRIAL YEARS

Sunsets (Were the spectacular sunsets of the time due to dust from Krakatoa?)

Root nodules and their bacteria

Plant galls

Grasses, carrots, gardenias, barley

Algae, protozoa in drinking water, hydrogen peroxide in living organisms

*Fermentation, butanol fermentation, Saccharomyces associated with beer, Schizosaccharomyces octosporus

Lactase, maltase, blue cheese bacteria, kefir

Photobacteria, sulfate reduction

*Methods: auxanograms, gelatine plates, Chamberland filters, sampling stratified cultures, microbiochemical analysis.

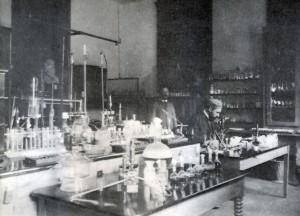

When his sisters, Henriette and Johanna, visited him in his laboratory, Henriette reported that he “sat there, surrounded by a mass of retorts, bottles and glasses, boxes, corks and heating apparatus, so that it looked like the workshop of an alchemist”.

Eventually, Van Marken and a few others managed to persuade the Delft Polytechnic (now Delft University of Technology) that they really needed a Department of Microbiology with Beijerinck as its Professor. Until his new lab was ready, he continued to use the laboratory at the Yeast Factory. Their support continued for the rest of his life – when Beijerinck retired, the Yeast Factory paid for the construction of a laboratory in the garden of his retirement house in Gorssel.

Applied Botany

After his appointment as a Professor, Van Iterson initially worked in Beijerinck’s lab , but in 1908 he was given space in a house at Oude Delft 81, a building used for temporary accommodation by the Polytechnic. As can be seen from the photographs, the rooms were small and not really suitable for use as teaching laboratories. The office, and the library were tiny, and the greenhouse was far too small for a Department called “Applied Botany”. It wasn’t until 1911, when he was offered a job in Java, that the Polytechnic agreed to start work on a purpose-built laboratory and Botanic garden. Both finally opened in 1917. At the time of writing, the laboratory is now part of Delft University’s Department of Biotechnology, but the Department will move to a new building later this year. The Garden’s website is HERE.

- Office

- Library

- Greenhouse

- Laboratory

- Research laboratory

- Teaching lab

Delft’s first microbiologist – Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

Although the Delft School of Microbiology only dates back to Martinus Beijerinck and the late 19th century, it seems churlish to ignore Antonie van Leeuwenhoek on a blog discussing Delft microbiology just because he was 200 years too early. He was not a teacher and indeed actively resisted explaining his methods, but he did publish copiously about everything he saw with his magnifying glasses and simple microscopes, making him the first microbiologist (although not the first microscopist).

Today, van Leeuwenhoek is generally mentioned in connection with the discovery of microorganisms. However, his studies were much broader than that. He dissected insects, and examined anything that would fit on his microscope. His first letter to the Royal Society illustrates this clearly as it covers the sting, head and eye of the bee, and the structure of a louse as well as his observations of fungus that he said grew on leather, meat and other things.

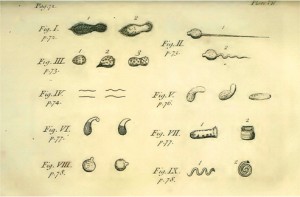

Van Leeuwenhoek’s microbiological discoveries began in 1674 when he examined samples from the cloudy water of the Berkelsemeer, a lake near Delft that no longer exists, and found his famous “little animals”. His discovery of bacteria probably dates from his pepper water experiments in 1676, when he reported seeing extremely small animals among the others – a copy of the drawing that accompanied this letter was published by Henry Baker, and is shown here. “Fig IV” is probably the first appearance in print of a bacterium.

- Bright field microscopy of living protozoa

- Dark field microscopy of algae

- Facsimiles of van Leeuwenhoek microscopes

The film clip here – www.youtube.com/watch?v=OniSF8QrHac – shows what can be seen with facsimiles of van Leeuwenhoek microscopes.

And there’s an excellent website about our Founding Father here: http://lensonleeuwenhoek.net/

Recent Comments