Posts in category The Museum/Archive

Van Iterson’s wall chart collection.

In the days before the easy projection of images, wall charts were the usual manner of illustrating lectures and practical classes. This photo shows the autumn 1941 practical on microscopical research of living plants and plant products, with wall charts in use on the back wall. Prof van Iterson can be seen standing in the far left corner of the room.

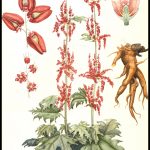

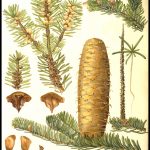

The Archive has a large collection of these wall charts, and I’ve previously shown some of the printed ones as well as some by Henriette Beijerinck. The original wall charts for Van Iterson’s Department were produced by at least 15 people, not all of whom signed their work with their full names. They range from beautiful watercolours of useful plants to diagrams and tables – everything a Professor of Applied Botany could need for his lectures.

- Ornamental rhubarb by Karin Mauve, 1920s

- Poppy by Hilda Kern, 1940s or 50s

- Almonds by ? Bongers, 1923

- Silver spar pine by J. Mouton, 1920s

- Peanuts by Sluyterman, 1920s

- Cotton by Karin Mauve, 1920s

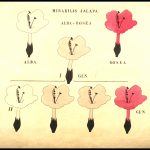

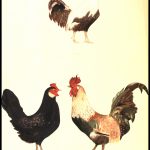

Like Beijerinck and Kluyver, in those days before the discovery of DNA, Van Iterson was interested in heredity and variation, and we have a series of watercolours illustrating Mendelian genetics, gender dimorphism and mimicry.

- Mendelian cross of white and pink Mirabilis jalapa. Unknown.

- Cross of Italian and Plymouth Rock chickens

- Butterfly mimicry by J. Mouton, 1920s?

Researching and cataloguing the wall chart collection was a great labour of love by Truus ten Hoopen-van Hulsentop. If anyone can tell us anything more about the various artists, we’d be delighted to hear from you.

Beijerinck’s office (and the neighbours)…

At long last, the Beijerinck Museum is ready for visitors – indeed several groups, including the Dutch Microscopy Society and guests from the Queckett Microscopical Club, have had sneak previews. Also known as “Beijerinck’s Office” (Kamer van Beijerinck), it will only be open to escorted groups as we don’t want to spoil the atmosphere by putting everything into locked display cabinets. Some of our microscopes are now on display in the foyer of the Mekelzaal, the main conference room of the Science Centre.

- Beijerinck's office 2

- Beijerinck's office 1

- Microscope display

- Monuments to Beijerinck, Van Iterson, Kluyver and Van Rossem

At the end of BioDay, a meeting organised to celebrate the TUDelft’s 175th birthday, the Museum was re-opened by Professor Karel Luyben, Rector Magnificus of the University, ably (?) assisted by someone claiming to be Prof Beijerinck’s assistant…

- Opening the museum

- Bioday

This seems like a good moment to take a look at our new surroundings. We are housed on the second floor of the Delft Science Centre. The building was originally the Faculty of Mining. It’s very easy to feel at home here as, like Prof van Iterson’s section of our previous building, our new home dates from the early 20th century and the design is very similar. The view from our windows is a great improvement!

- Science centre

- Mining

The main part of the Science Centre displays the modern achievements of Delft University of Technology and a range of prototypes (including Delft’s famous solar powered car) can be seen as well as displays that can be operated by the visitors. You can try improving the shape of an aircraft wing or use the driving simulators, among many other things – the exhibition often changes. The robotics lab is ever popular, as are the workshops where school groups (among others) come to try things out. For example, the Dutch Microscopy Society will be running a public workshop (about how to make botanic preparations (Wollemia nobilis) and look at them under the microscope) from 14:00-16:30 on 7th May (2017). Participants will only pay the Science Centre entrance price. The details are here: www.sciencecentre.tudelft.nl/nl/bezoek/agenda/event/detail/gratis-microscopie-workshop/. It’s in Dutch but the site will allow you to copy the text for pasting into Google translate (which is always amusing….).

- The Science Centre's main hall

- climber

- Robotics

The TUDelft has always had a number of internationally important collections which started life as the working tools and products of its research departments. Among them, the minerals collection from the Faculty of Mining (which dates from the middle of the 19th century) is remarkably beautiful. It is housed, in its original display cases, in rooms next door to the Beijerinck Museum and in cabinets in other public parts of the building. Like the Beijerinck Museum, the Minerals Collection is open to escorted groups.

- Minerals museum

- Minerals exhibition

- Garnets

- Amethyst

Just around the corner from the Science Centre is Delft’s Botanic Garden. Founded by Prof van Iterson with support from Prof Beijerinck, it was set up to provide plants for research in the Department of Applied Botany and is 100 years old this year (2017). Apart from their permanent collection (which includes an apiary), they frequently have exhibitions ranging from pottery through products made from plant material to photography. Their website is here: http://www.botanischetuin.tudelft.nl/en/

- Botanic garden

- Garden entrance

The Science Centre’s website with opening times and other information is here http://www.sciencecentre.tudelft.nl/en/.

Delft, the Home of Microbiology

An exhibition at Van Leeuwenhoek’s resting place.

2017 is the 175th anniversary of the founding of the Polytechnic School that eventually became Delft University of Technology. The University is celebrating with a 175 day Lustrum, much of which will focus on the Life Sciences. It is also 100 years since Van Iterson founded the Delft Botanic Garden on the land behind his laboratory.

We are beginning the celebrations with a look at the history of microbiology and the biosciences in Delft, from the 17th to the 21st centuries. The exhibition will run until 26 February, 2017.

This will take the form of an exhibition in the area around Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s grave in the Oude Kirk.

- Delft's Old Church

- AJ Kluyver at the grave of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek

The text on the poster boards is in Dutch, but there are also English language handouts. It includes 20th century teaching microscopes, a cross section of an electron microscope and 3-D scanned replicates of a Van Leeuwenhoek microscope and the Delft telescope.

The exhibition offers a taster of the achievements of Delft microbiologists and introduces some of the people who helped and supported them. For example, we might never have heard of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and his little animals without Reinier de Graaf, the doctor who introduced van Leeuwenhoek to the Royal Society of London, publishers of much of his work. Jacques van Marken not only brought Beijerinck to Delft to establish his industrial microbiology laboratory, he was also one of the people instrumental in creating the Department of Microbiology and Professor’s Chair for Beijerinck at what was then the Delft Polytechnic.

- Reinier de Graaf

Medicinae Doctor

- Jan and Agneta van Marken

Many others have provided help, support and encouragement, but the silent contributor to the history of microbiology is the City of Delft itself. Many very well-studied microorganisms were found for the first time in samples from Delft’s canals, soil and from industrial sources, even now.

- Th old city gate

- Wastewater bioreactors

Over 300 years ago, before Van Leeuwenhoek found his little animals, the city was already a hotspot in scientific research-for example Stevin and de Groot dropped different lead balls off the tower of the New Church and proved that they hit the ground at the same time 3 years before Galileo did the same experiment from the tower of Pisa!

Auld lang syne, new beginnings and a mystery solved

After weeks of chaos, mountains of used packing paper and bubble wrap, disappearing essentials and wandering packing boxes, we’re beginning to see the end of the chaos… The regular visits to the old lab to look for misplaced odds and ends have finished, and the building is now occupied by asbestos removal experts. Curiously, the information monitors are still announcing lectures and other happenings!

- The asbestos removers have moved in.

- But the monitors carry on!

Meanwhile, back at the Science Centre, order has (mostly) appeared from chaos. Small jobs such as picture hanging still need to be done, but we can actually find things and we’ve already had our first overseas visitor!

- Room with a view!

- Photos of Kluyver's contacts waiting to be hung

- Slowly getting sorted out

As you can see from the photos, the museum and archive spaces are a little smaller, but we have a good cellar for safe storage of items that we don’t need to use very often, so things don’t look as cluttered as they did. Working in well-lit rooms doesn’t feel quite natural yet – those who visited the old museum will remember that we had tiny windows covered with thick green anti-UV blinds and permanent electric lighting. Thanks to UV-resisting film on the glass, we can now see out of the windows, and even work by daylight!

- Equipment waiting for just the right place..

- Archive boxes and the wall chart cabinets

- The luxury of an office

We even have a proper office instead of odd desks squeezed in wherever we could – luxury!

Mystery solved

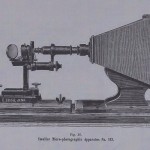

Returning to the strange microscope of my previous post, I think that I have solved the mystery. While cleaning it, I noticed that the heavy stand is not of the same quality as the rest of the microscope, and (unlike the rest of the microscope parts) does not have the Carl Zeiss Jena (CZJ) name or number. Also, the screws and hooks holding the four lenses and condensers are a bit rusty (and thus not up to CZJ’s standard). I then came across the diagram below in the 1885 CZJ catalogue, and realised that what we have is a home-made version. The microscope in the diagram only has a single condenser, but whoever made ours obviously felt that if a thing was worth doing, it was worth overdoing!

- Our home made version

- Photo microscope from CZJ in 1885

- 19th century "jug handled" Zeiss microscope

- 1880s Glass negative showing Rhizobium

What we have is a standard CZJ “jug handled” microscope from the end of the 19th century, lying on its back and converted for micro-photography. Sadly, we don’t have the camera, but it does explain how the early photographs (beginning in the 1880s) in our collection of glass negatives were made.

Professor Beijerinck’s samples have left the building…

The day has arrived. The packing is finished, the furniture must be dismantled and then it’s time to move to our new rooms. It’s hard to understand how 3 smallish rooms can require so many boxes to empty them!

Most of the collection is being professionally moved, of course, but Prof Beijerinck’s gall and root nodule samples (preserved in alcohol) are too fragile for the vibration in a lorry and so a team of volunteers carried them around the corner to our new abode.

We plan to reopen in the Autumn, look for us at the Delft Science Centre on Mijnbouwstraat.

What was this microscope used for?

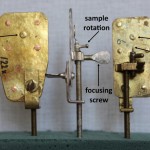

Discovering rare or unusual microscopes has become almost routine since we began packing the collection, but this one has me (and everyone else who has visited) baffled.

It seems to be a “jug handled” Carl Zeiss Jena microscope from the late 19th/early 20th century. However, it is mounted on its back rather than on a foot (1). Moreover, in place of the usual single condenser, there’s what seems to be 2 lenses of different strengths and 2 condensers (2), hinged so that any of them can be used to light the preparation (3). There’s an additional lens which can swing over the usual ocular (4).

Has anyone any idea what it was used for?

- 1: side view

- 2: "foot"end

- 3: "condensers"

- 4: ocular end

From “out of date junk” to “exciting and rare” – our microscope collection

At the moment, sorting out the cupboards before our move has become very exciting as I’ve reached the microscope collection. Much of it was stored in the 1950s when the Laboratory of Microbiology moved from its original building, and has rarely been disturbed since then. Some of the microscopes date from the late 19th century, and even some of the 20th century ones are more interesting than might be expected.

The youngest of the companies represented in our microscope collection is probably the least well-known, especially outside the Netherlands.

Bleeker Nedoptifa

Founded by Dr Caroline E. (Lili) Bleeker and Gerard Willemse in 1939, Nedoptifa rapidly became known for the high standard of their optical products. They began with the production of binoculars for the Dutch army, but production was interrupted by WW2. Most of their microscope production seems to have been after 1945, when the “Nedoptifa” name came into use. The company cooperated with the Nobel prize-winner, Frits Zernike, in the development of phase contrast microscopy and held his patent on phase contrast microscopes. Bleeker retired at the end of 1963, the company was eventually taken over by a Delft firm and then in 1978 the factory in Zeist was closed.

Kluyver’s group seems to have used the basic Nedoptifa microscope for teaching – we have quite a few of them. Most of them have the standard circular stage, but a few are square. We also have one of their very early binocular microscopes as well as monocular and binocular phase contrast microscopes. Most of them, with the exception of the binocular phase contrast microscope, seem to have been use in in the laboratory before 1955.

Note added later: Disappointingly, after a visit in mid-June from Peter Paul de Bruyn, an expert on Bleeker microscopes, it seems that the microscopes whose boxes proclaimed them to be phase contrast microscopes do not have the necessary lenses or fittings. They may appear as we complete the packing of the collection, but it’s beginning to look unlikely.

- Bleeker Nedoptifa binocular microscope

- Early Bleeker Nedoptifa "phase contrast" microscope

- Bleeker "phase contrast" microscope from the 1960s

Carl Zeiss Jena

This famous old microscope manufacturer needs no introduction. In what is probably our most famous portrait of Prof Beijerinck, he is clearly using one of their “jug handled” microscopes. Others in our collection are in the Zeiss catalogues of the late 19th century.

- Prof M.W. Beijerinck in his laboratory

- 19th century "jug handled" Zeiss microscope

We also have some more unusual examples of their work including a “horizontal microscope” (intended for examining living plants) and a binocular microscope fitted with a prism on the right ocular to aid the drawing of samples.

- Horizontal Zeiss microscope

- Zeiss drawing microscope

I really shouldn’t have favourites, but I must admit a fondness for the very heavy preparation microscope that turned up in a battered old wooden box on top of a cupboard. When it is taken out of the box, the eyepieces on the right flip up, giving a forerunner of our modern stereomicroscopes which can be found in the 1902 Carl Zeiss Catalogue. There are 2 sets of lenses and oculars. During dissections, the microscope can be moved backwards and forwards along the metal bar.

Ernst Leitz Wetzlar

Another famous old company, Leitz seems to have been a favourite with Professor van Iterson. Among the microscopes from this company are a “measuring microscope”, a preparation microscope with wrist supports and the microscope (with an extensive collection of extra attachments) that he used after he retired.

- Leitz "measuring microscope"

- leitz preparation or stereo microscope

- Leitz microscope with one of two boxes of attachments

Other companies

Other microscope makers are mostly represented by single instruments, so I will only show two of the most spectacular. First is the interference microscope made by Cooke, Troughton & Simms from the Van Iterson collection. This microscope is accompanied by a set of extra attachments and filters.

- Inteference microscope by Cooke, Troughton & Simms

- Attachments for the Cooke et al microscope

And lastly, one of the most unusual microscopes in our collection, a reversed microscope made by Nachet & Fils of Paris. The sample lies on the stage and can be illuminated from above, with the observer’s light path underneath the stage. It appears in the 1898 Nachet catalogue. This microscope was given to the collection by Dr and Mrs ten Hoopen, both of whom worked in the Department of Applied Botany before volunteering to help with the Archive and Museum after they retired.

The Delft School of Microbiology Archive owes a huge debt to both of them. Truus undertook two major tasks. First she restored our enormous collection of glass negatives (see the blogpost “Glass negatives galore!”) after they all got damp during asbestos removal in the attic where they were stored. She then went on to research and catalogue our collections of original and printed botanic and microbiological wall charts (see blogposts “The art of Henriette Beijerinck” and “Educational Wall Charts – where are they now?”). Meanwhile, Hens catalogued the microscopes and other equipment (we have the most amazing range of pH meters, for example) in our collection.

Without Truus and Hens ten Hoopen, we would know a lot less about the Collection than we do.

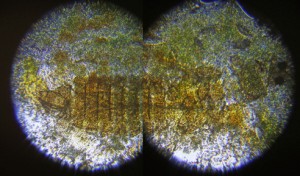

Playing with facsimile Van Leeuwenhoek microscopes

Since most of my available time is currently vanishing into preparing the Delft School Archive and Museum for its move to Delft’s Science Centre, I thought that a simple blog showing some of the photos I’ve taken with my facsimile Van Leeuwenhoek microscopes might be nice this month.

By the way, I’ve been asked why I keep the photographs on this blog fairly small. The reason is simple – I’ve had some problems with plagiarism and this is an attempt to limit what people can do or claim with my work without the high resolution versions.

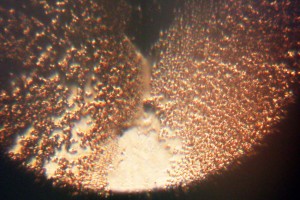

I have 5 Van Leeuwenhoek facsimiles with magnifications ranging from 68x-303x, and have been trying to repeat some of his experiments as closely as possible (it’s a good way to spend a wet weekend!). The first 2 pictures show the structure of the microscopes and my photographic setup. Ideally, one needs a camera that can cope with single point metering, and a macro lens also helps with short focusing distances. The microscope is clamped in front of the camera lens, side-on. The piece of cardboard (with a 1 cm hole in it) is there to protect the camera’s light meter because that lamp was much bigger than the microscope. I’ve recently been finding it easier, especially with the stronger lenses, to use a small LED torch.

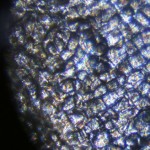

Fossil microorganisms can be very useful for comparing methods as they don’t dry out, swim away or otherwise change. Here you can see a vorticella-type protozoan (L) and diatom preparations under bright (C) and semi-dark field (R) lighting

Van Leeuwenhoek’s first observation of microorganisms came from his examination of a water sample from a shallow lake called the Berkelsemeer. This lake no longer exists, but a sample from a similar lake near Delft (the Delftsehout) provided this picture (one of the first I took) of blue-green algae and a rotifer on the right. The black circle is an air bubble.

Van Leeuwenhoek did a lot of work on the formation of crystals of different sorts, and the next 2 photographs show the same table salt crystal under bright (L) and semi-dark (R) field lighting. My results agreed with Van Leeuwenhoek’s observation that you get smaller crystals if you let them form slowly by letting the saturated solution evaporate at room temperature rather than by heating it.

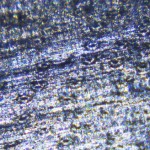

The next picture shows red blood cells that I’d dried onto a coverslip. I only noticed after I’d taken the photograph that the little torch had slipped a bit, but I rather like the odd lighting effect.

Thus far, my attempts to make thin enough slices of plant materials to examine properly have not been very successful. These photos show my best efforts for carrot root (L) and leek leaf (R). I’m reluctant to cheat by using a microtome, so will have to keep practising!

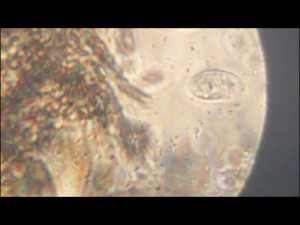

As Van Leeuwenhoek also complained, the shallow depth of field (or focus) of the stronger microscopes can be a real problem. I haven’t been very successful with taking photos of living microorganisms using the 303x lens. They tend to swim out of focus before I have time to trigger the shutter, so the least frustrating thing is to make short films and then use single frames from the film. This image shows bacteria and a hunting ciliate protozoan from a pepper water sample.

Finally, a lobster larva from a seawater sample. It was either long dead, or a shed skin as the whole thing was covered by a thin layer of algae. I had to take 2 photographs and then join them afterwards– I obviously need to get a weaker microscope!

The parting of the ways…

At the end of March 1958, two years after Kluyver’s death, the Laboratory for Microbiology moved out of the building where he and Beijerinck had worked. Kluyver had been heavily involved in the design and planning of the new building, but it was his successor, Torsten Wikén, who took possession.

- Kluyver memorial

- Last day at the old lab, Prof Wiken central with a cigar

- Delft School memorial on old lab, Kanaalweg

The new laboratory was attached to the new Department of Biochemistry, the Department of Applied Botany previously erected for Van Iterson and the associated Botanic Garden dedicated to applied botany.

- The new Microbiology Laboratory in 1958

- The Beijerinck ceiling in the entrance to the Laboratory for Microbiology, 1958

Professor Wikén’s new office was given new furniture, and the contents of the office used by Beijerinck and Kluyver were stored in a purpose-built room in the microbiology attic. Since the 1980s, this collection has gradually been organised and merged with similar material left by Van Iterson when he retired and a few related donations, giving us what is known today as the Delft School of Microbiology Archives and the Museum known as the “Kamer van Beijerinck” (Beijerinck’s office). None of it would have been possible without the hard work of a legion of volunteers who have sorted and researched different areas of the collection.

The collection has attracted visitors ranging from individual researchers from as far afield as the USA and Japan to biotechnology students in their first year with their parents and visitors from schools. It’s provided material for TV programmes, exhibitions, publications and postage stamps as well as a couple of PhD theses… Visitors to the Department of Biotechnology have frequently been brought to see the collection during their visits, as have participants in some of the Delft Advanced Courses.

All good things eventually come to an end, and it is finally time for the Archive-Museum and the Department of Biotechnology to part company. Biotechnology is moving to a brand new Faculty building on the outskirts of Delft, uniting with other Faculty Departments. The Archive-Museum is moving around the corner to the old Department of Mining building, now the Delft Science Centre where the collection will occupy second floor rooms over the main entrance, next door to the minerals collection of the Department of Mining.

- Artist's impression of the new Faculty building

- Delft Science Centre with new Kamer van Beijerinck, 2nd floor with balcony

Regular readers of this blog will know that digitisation and cataloguing of the collection has been an on-going process and we’ve frequently been surprised as volunteers have found manuscripts and odd equipment as they’ve catalogued the contents of boxes. As we prepare for the move this is still true, and readers will no doubt be hearing about some of our more unusual discoveries (e.g. the papers relating to the unmasking of a cold war spy in the Department) in later posts.

Saying farewell to the Julianalaan will be sad in some ways (most of my scientific career was spent there), but our new rooms will be better lit and considerably less dusty. The Museum will be more accessible as it will no longer be necessary to walk through an active biotechnological laboratory to reach it. Last and not least, the move is giving us a chance to sort the document collection more logically, something that researchers who’ve visited us in search of specific documents will appreciate!

Recent Comments