Posts in category G. van Iterson jr

The parting of the ways…

At the end of March 1958, two years after Kluyver’s death, the Laboratory for Microbiology moved out of the building where he and Beijerinck had worked. Kluyver had been heavily involved in the design and planning of the new building, but it was his successor, Torsten Wikén, who took possession.

- Kluyver memorial

- Last day at the old lab, Prof Wiken central with a cigar

- Delft School memorial on old lab, Kanaalweg

The new laboratory was attached to the new Department of Biochemistry, the Department of Applied Botany previously erected for Van Iterson and the associated Botanic Garden dedicated to applied botany.

- The new Microbiology Laboratory in 1958

- The Beijerinck ceiling in the entrance to the Laboratory for Microbiology, 1958

Professor Wikén’s new office was given new furniture, and the contents of the office used by Beijerinck and Kluyver were stored in a purpose-built room in the microbiology attic. Since the 1980s, this collection has gradually been organised and merged with similar material left by Van Iterson when he retired and a few related donations, giving us what is known today as the Delft School of Microbiology Archives and the Museum known as the “Kamer van Beijerinck” (Beijerinck’s office). None of it would have been possible without the hard work of a legion of volunteers who have sorted and researched different areas of the collection.

The collection has attracted visitors ranging from individual researchers from as far afield as the USA and Japan to biotechnology students in their first year with their parents and visitors from schools. It’s provided material for TV programmes, exhibitions, publications and postage stamps as well as a couple of PhD theses… Visitors to the Department of Biotechnology have frequently been brought to see the collection during their visits, as have participants in some of the Delft Advanced Courses.

All good things eventually come to an end, and it is finally time for the Archive-Museum and the Department of Biotechnology to part company. Biotechnology is moving to a brand new Faculty building on the outskirts of Delft, uniting with other Faculty Departments. The Archive-Museum is moving around the corner to the old Department of Mining building, now the Delft Science Centre where the collection will occupy second floor rooms over the main entrance, next door to the minerals collection of the Department of Mining.

- Artist's impression of the new Faculty building

- Delft Science Centre with new Kamer van Beijerinck, 2nd floor with balcony

Regular readers of this blog will know that digitisation and cataloguing of the collection has been an on-going process and we’ve frequently been surprised as volunteers have found manuscripts and odd equipment as they’ve catalogued the contents of boxes. As we prepare for the move this is still true, and readers will no doubt be hearing about some of our more unusual discoveries (e.g. the papers relating to the unmasking of a cold war spy in the Department) in later posts.

Saying farewell to the Julianalaan will be sad in some ways (most of my scientific career was spent there), but our new rooms will be better lit and considerably less dusty. The Museum will be more accessible as it will no longer be necessary to walk through an active biotechnological laboratory to reach it. Last and not least, the move is giving us a chance to sort the document collection more logically, something that researchers who’ve visited us in search of specific documents will appreciate!

Delft’s Biological Labs 2: The originals..

Sadly, there are no pictures of the first “microbiological laboratory” and the building was demolished at the start of the 1890s, but by collecting the occasional descriptive comments from Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s letters, we can gain a glimpse of the room where so many types of microorganism were seen for the first time. The following is an extract from our book “Antoni van Leeuwenhoek: Master of the Miniscule” which is scheduled for publication by Brill, Leiden (Brill.nl) in April, 2016.

Van Leeuwenhoek’s home and workshop

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek worked in his comptoir. The word literally means a counting or writing room, but it was actually his workshop. It was located in an annex to his house so that he would not be disturbed. The room was partitioned off with wainscoting, with a hole to accommodate the spring pole of his lathe. The bottom two of the four windows overlooking the street could be opened upwards, and were fitted with wooden shutters. His workshop could be closed off “so that little or no air enters from outside”, but if he was working with a candle, he preferred to open them a little, and cover the window with curtains.

His letters and the inventory of the house compiled after the death of his daughter Maria reveal some of the equipment and materials that he used. As well as his lens and microscope making equipment, there was a small furnace to extract gold and silver from ore, a barometer, a salt water aquarium, sharp blades, chemicals (including the distillate “brandewijn” for conservation and saffron for colouring), and a collection of specimens ranging from minerals to the testicles of a rat preserved in spirits. He had a balance with weights, a glass-blowing table with a lamp, and an anvil for the production of his microscopes, and all of his surveying equipment.

Many of the objects that Van Leeuwenhoek studied came from the immediate surroundings of his home. He had two gardens, one adjoining the house with a well and another outside the city. He kept a green parrot for a long time and examined the excrement of the sparrows in his yard after feeding them. Delft’s fish market was just across the canal from his house. Since he regularly attended the dissection demonstrations at the neighbouring Anatomy Theatre, it seems likely that he brought samples home. Additionally, in a few of his letters he mentioned that sailors returning from voyages brought him exotic samples.

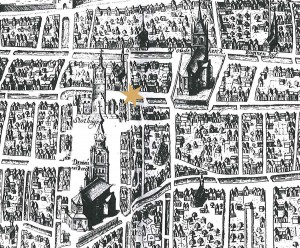

The star shows the position of Van Leeuwenhoek’s house in relation to the Town Hall, where he worked, the marketplace and the Old Church where he is buried.

The Microbiology Laboratory

Beijerinck originally came to Delft in 1885 to set up and run a microbiological laboratory in J.C. van Marken’s Yeast Factory. Van Marken and his wife were enlightened employers, providing their workers and their families with on-site houses, education, medical and social facilities. Van Marken made it a point of honour to keep all of his staff informed about the factory by means of an internal paper called “De Fabrieksbode”. In 1885 he wrote an article about the need for proper bacteriological studies, edited extracts of which follow:

“I would like to explain the need for the appointment of Dr. Mr. W. Beijerink as Chief of the Bacteriological Laboratory of the Yeast Factory…..

I have previously discussed the idea that “life is a struggle”, in this case between yeast and against harmful bacteria. The day on which the last harmful bacteria has been expelled from our

factory will be a cause for celebration and a public holiday….

We would have a quality supply of yeast, which would overcome the sharpest competition; our yeast would be able to circle the world in 80 days, without spoiling.

So fight the harmful bacteria!“

Van Marken’s attitude to results seems remarkably relaxed, contrasting with the attitudes of modern industry. He went on to say:

”Whatever the case, the arrival of the scholar, Dr Beyerinck must be appreciated in more ways than one. We must not have exaggerated expectations of his activities in and for our factory, but have faith that in maybe one, five or even ten years, some day a ray of light will be cast into the darkness of the fermentation business and bring incalculable advantages to our company.”

It cannot be claimed that Beijerinck was happy as an industrial scientist. He felt responsible if errors incurred financial losses, and his interests were much wider than required by his job. As can be seen from the table below and his laboratory journals, he seems to have normally had several unrelated lines of research running at any one time. Only the rows marked * involved work needed by the Factory.

TOPICS OF PUBLICATIONS THAT APPEARED DURING BEIJERINCK’S INDUSTRIAL YEARS

Sunsets (Were the spectacular sunsets of the time due to dust from Krakatoa?)

Root nodules and their bacteria

Plant galls

Grasses, carrots, gardenias, barley

Algae, protozoa in drinking water, hydrogen peroxide in living organisms

*Fermentation, butanol fermentation, Saccharomyces associated with beer, Schizosaccharomyces octosporus

Lactase, maltase, blue cheese bacteria, kefir

Photobacteria, sulfate reduction

*Methods: auxanograms, gelatine plates, Chamberland filters, sampling stratified cultures, microbiochemical analysis.

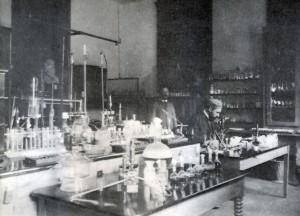

When his sisters, Henriette and Johanna, visited him in his laboratory, Henriette reported that he “sat there, surrounded by a mass of retorts, bottles and glasses, boxes, corks and heating apparatus, so that it looked like the workshop of an alchemist”.

Eventually, Van Marken and a few others managed to persuade the Delft Polytechnic (now Delft University of Technology) that they really needed a Department of Microbiology with Beijerinck as its Professor. Until his new lab was ready, he continued to use the laboratory at the Yeast Factory. Their support continued for the rest of his life – when Beijerinck retired, the Yeast Factory paid for the construction of a laboratory in the garden of his retirement house in Gorssel.

Applied Botany

After his appointment as a Professor, Van Iterson initially worked in Beijerinck’s lab , but in 1908 he was given space in a house at Oude Delft 81, a building used for temporary accommodation by the Polytechnic. As can be seen from the photographs, the rooms were small and not really suitable for use as teaching laboratories. The office, and the library were tiny, and the greenhouse was far too small for a Department called “Applied Botany”. It wasn’t until 1911, when he was offered a job in Java, that the Polytechnic agreed to start work on a purpose-built laboratory and Botanic garden. Both finally opened in 1917. At the time of writing, the laboratory is now part of Delft University’s Department of Biotechnology, but the Department will move to a new building later this year. The Garden’s website is HERE.

- Office

- Library

- Greenhouse

- Laboratory

- Research laboratory

- Teaching lab

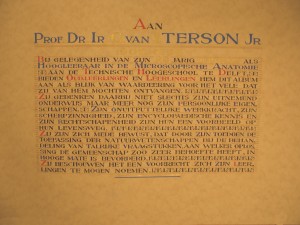

Celebrating Professors

During the first half of the 20th century, it seems to have been customary to make certificates, posters or books to commemorate special events. The Archive includes a number of photo albums showing laboratories in the University or even abroad, but three examples stand out, not least because of the considerable amount of work that went into them.

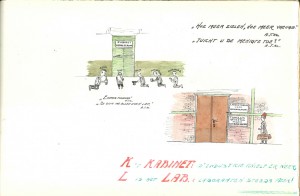

The first is a book made for Kluyver by three of his pupils (van Niel, Leeflang and Struyk) a few years after he became Delft’s Professor of Microbiology. The book compares Beijerinck’s 19th century approach to the wonders to be found in 1 gram of soil with Kluyver’s 20th century approach to the wonders associated with 1 gram of carbinol. That’s not students kneeling outside the Professor’s door in the 4th page, but representatives of industry!

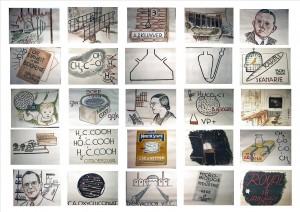

The second is a handmade poster (about the size of a large double bed) that was made to mark the 25th anniversary of Kluyver’s inaugural lecture. It shows notable features from those 25 years, including sketches of the laboratory, Kluyver’s most famous work (The Unity in Diversity) and his inaugural address (“Rede”) in which he emphasized the importance of applied research. Every rectangle represents a story.

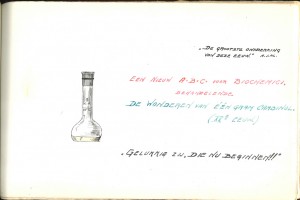

The Kluyver Flask (still used for growing submerged, well-mixed cultures) and a shaker for closed jars containing oxygen-free cultures are shown. During the Dutch “Starvation Winter” at the end of World War II, Delft’s Yeast and Spirits Factory gave their staff soup made from yeast extract at lunch time, and as one of their advisors, Kluyver regularly benefited from this at weekly meetings. Lastly, at a time when it was usual to stand if a Professor came into the room, the staff’s affection for Kluyver shines through in several squares teasing him about his smoking!

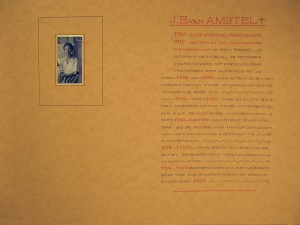

A book to mark van Iterson’s 25th anniversary as a Professor also falls into this category despite being essentially a photo album because the makers included all of his PhD students, postdocs and co-workers from other countries, showing who they were, what they did and what happened to them afterwards. van Iterson’s conviction that the primary job of a Professor is to teach is obvious from the fact that there’s 160 pages, each with one or more person on it. The example here shows J.E. van Amstel, the first woman to be granted a Doctorate in Delft.

Educational wall charts – where are they now?

During the second half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, a number of companies produced wall charts as teaching aids. The theme and quality varied enormously, but most of the ones intended for bioscience education are not only very detailed, but generally beautiful in their own right. They were sold singly, or by subscription. Subscribers were sent the charts as they became available (often 1-2 per year), together with explanatory books.

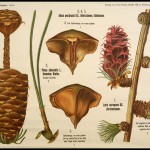

Delft’s collection includes several complete series, including those by Kny, Dodel-Port and the series known as the Tabulae Botanicae (often attributed to “Blakeslee et al”, but most of the posters are signed by R. Erlich). However, we also have a number of incomplete series which might be represented by a single example, or a few posters. Some complete series are available elsewhere. For example, the conifers chart shown here is number 16 of 50 by Albert Peter – a complete series is held by the University of Bourgogne. However, many seem to have been forgotten.

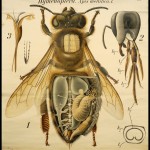

With the help of collections around the world, it has recently been possible to assemble an electronic complete series of Pfurscheller’s zoological charts (here represented by the fly). Representatives from other partial series are shown here:

The Mycorhiza chart is number 10 from “Pflanzenphysiolgische Wandtafeln” by Frank & Tschirch (we have 1-10 of 60), most of the series is held by the University of Utrecht, among others.

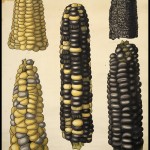

The sweetcorn is number 3 in series C of a set for general biology by Haecker & Mülberger. Series A and B are both currently known by single examples, and Delft currently has 1-4 of series C, the size of the complete set is unknown.

The flowers come from a set by O.W. Thome (Delft has numbers 15 & 23).

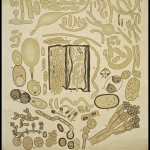

The microorganisms come from a series by W. Henneberg about microorganisms with positive or negative impacts on the fermentation industry. This is number 6, vinegar fermentation. Delft has 8 of an unknown number.

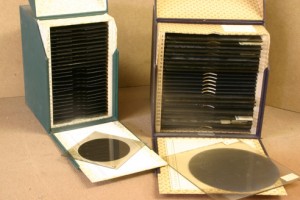

Glass negatives galore!

Our glass negative collection (about 27,000 of them) dates from the mid-1880s to the 1960s (when they were being used with the electron microscope. It covers a remarkably wide range of topics including Beijerinck’s gall wasps, light microscopy, travel (especially van Iterson’s working trip to Indonesia) to images from publications – essentially what any group of Professors would have in their Powerpoint collections today. The quality of the images is amazing – it has been possible to enlarge pictures to A0 without grain or blurring.

Later posts will showcase the individual collections of the three Professors, this is just a taster to show examples of what we have.

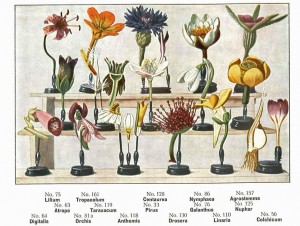

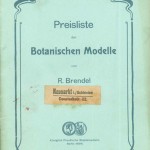

Brendel flower models

The collection includes about 20 of the flower models made by Robert and Reinhold Brendel in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The models are made from papier-mâché with other materials including plaster, glass beads, wood, cotton and rattan added to give detail or texture. They can be taken apart to reveal internal details (although they’re not always simple to put back together again). The Brendels were advised on the accuracy of their models by various Professors, depending on what the particular model was intended to show. As well as plants, models of fungi, yeast and bacteria were eventually included.

Dealers included the models in their own catalogues, but Delft has the only known surviving Brendel catalogue, issued in Berlin in 1913.

Recent Comments